Wednesday, May 15, 2013

On

the farm Langverwacht there is a monument to the 23 New Zealander soldiers, who

died in an encounter with a Boer commando on the night of 23rd and

24th February 1902. Sometime in 2000 the monument was destroyed by a

falling tree, one of the two oak trees planted around the site of the mass

grave. A grass fire had damaged and weakened the old oak. A high wind sometime

later did the rest. Built from local stone, cut to shape on the site, the cairn

had remained intact for 99 years from 1903 when it was erected. This was my

first sight of the ruined structure in 2002.

On

the farm Langverwacht there is a monument to the 23 New Zealander soldiers, who

died in an encounter with a Boer commando on the night of 23rd and

24th February 1902. Sometime in 2000 the monument was destroyed by a

falling tree, one of the two oak trees planted around the site of the mass

grave. A grass fire had damaged and weakened the old oak. A high wind sometime

later did the rest. Built from local stone, cut to shape on the site, the cairn

had remained intact for 99 years from 1903 when it was erected. This was my

first sight of the ruined structure in 2002.

The

monument was still intact in October 1999. A small gathering paid tribute to

the combatants of both sides on 11th October of that year. Willem

Naudé from Vrede arranged the ceremony and, in spite of making contact with the

New Zealand High Commission in Pretoria, nobody from New Zealand was able to

attend.

The

monument was still intact in October 1999. A small gathering paid tribute to

the combatants of both sides on 11th October of that year. Willem

Naudé from Vrede arranged the ceremony and, in spite of making contact with the

New Zealand High Commission in Pretoria, nobody from New Zealand was able to

attend.

Getting

the monument rebuilt was no easy task. The New Zealand Government Heritage Ministry

are the custodians of New Zealand’s war graves but this is no longer a war

grave. The remains of those buried in a mass grave at the foot of the monument

were re-interred in a Garden of Remembrance in the Town Cemetery in Vrede in

1965. However, the fact that Langverwacht was the first occasion when a

significant number of New Zealand soldiers lost their lives in a war on foreign

soil was a deciding factor. The Prime Minister, Helen Clark, in fact ordered

the rebuilding. Let into the base of the monument was a white marble plaque

with inlaid lead lettering giving the names of the fallen. The plaque had been

broken, fortunately into only two pieces. Finding the missing piece was the

easy part.

Sadly,

Willem Naudé passed away on 17th November 2008 without ever seeing

the rebuilt monument. His last visit was on 5th August 2008. Willem

had an abiding interest in Langverwacht and the history of Vrede and its

inhabitants. He wrote a book about the area during the Anglo Boer war which he

had privately printed. He made a number of contacts in New Zealand who supplied

many of the pictures that he used in his book. This was his last visit to the

site in company with the farm owner, Jan van Reenen and the New Zealand Deputy

High Commissioner, Mike Walsh.

Sadly,

Willem Naudé passed away on 17th November 2008 without ever seeing

the rebuilt monument. His last visit was on 5th August 2008. Willem

had an abiding interest in Langverwacht and the history of Vrede and its

inhabitants. He wrote a book about the area during the Anglo Boer war which he

had privately printed. He made a number of contacts in New Zealand who supplied

many of the pictures that he used in his book. This was his last visit to the

site in company with the farm owner, Jan van Reenen and the New Zealand Deputy

High Commissioner, Mike Walsh.

The

rebuilding of the structure was completed in November 2008. Certainly it was an

emotional moment for me when I saw the rebuilt cairn on this occasion. The two

pieces of the white marble plaque were joined together and replaced. A further

plaque has been placed to show the part played by the government of New Zealand

in bringing this project to completion. The construction crew is all smiles on

this occasion, like the New Zealand Deputy High Commissioner, Mike Walsh and

contractor, Gerna van Heyningen. Joseph Buthelezi, the man who lives on the

property and was in the 1997 picture, was present in 1965 when the remains were

disinterred. He pointed out to us exactly where the bodies of the slain were

buried. The monument was erected at the head of the mass grave.

The

rebuilding of the structure was completed in November 2008. Certainly it was an

emotional moment for me when I saw the rebuilt cairn on this occasion. The two

pieces of the white marble plaque were joined together and replaced. A further

plaque has been placed to show the part played by the government of New Zealand

in bringing this project to completion. The construction crew is all smiles on

this occasion, like the New Zealand Deputy High Commissioner, Mike Walsh and

contractor, Gerna van Heyningen. Joseph Buthelezi, the man who lives on the

property and was in the 1997 picture, was present in 1965 when the remains were

disinterred. He pointed out to us exactly where the bodies of the slain were

buried. The monument was erected at the head of the mass grave.

In

1937 five New Zealanders visited the site. They were brought to the monument by

Mr. Lombard who owned the farm where the battle had taken place. One of them

was the brother of Farrier Leonard Retter who was a casualty of the battle of

Langverwacht and whose name appears on

the monument. They found the monument to be in reasonable shape, looked after

by the South African Police from Vrede. The original name plaque, made from a

slab of sandstone was eroded and the names were illegible. A new plaque was

made of white marble with inlaid lead lettering at a cost of £18. This is the

plaque that has now been repaired and is now in the base of the obelisk.

In

1937 five New Zealanders visited the site. They were brought to the monument by

Mr. Lombard who owned the farm where the battle had taken place. One of them

was the brother of Farrier Leonard Retter who was a casualty of the battle of

Langverwacht and whose name appears on

the monument. They found the monument to be in reasonable shape, looked after

by the South African Police from Vrede. The original name plaque, made from a

slab of sandstone was eroded and the names were illegible. A new plaque was

made of white marble with inlaid lead lettering at a cost of £18. This is the

plaque that has now been repaired and is now in the base of the obelisk.

New

Zealand was the first of the colonial governments to offer troops for service

in the war that seemed imminent between the British Empire and the Boer South

African Republic. Prime Minister Richard Seddon’s motion to the House of

Representatives received overwhelming support. Following the motion’s adoption

the members rose to sing “God Save the Queen” and gave three cheers for Queen

Victoria. Seddon referred to New Zealanders’ duty “as Englishmen to support the

imperial cause.” New Zealand sent almost 6500 men and 8000 horses to South

Africa. The First Contingent arrived on 23rd November 1899 and was

quickly followed by four more contingents early in 1900. When it appeared that

the war was likely to be prolonged beyond the optimistic forecasts of the

middle of 1900, further fresh troops were sent, the Sixth Contingent arriving

in East London on 13th March and the Seventh in Durban on 10th

May 1901.

New

Zealand was the first of the colonial governments to offer troops for service

in the war that seemed imminent between the British Empire and the Boer South

African Republic. Prime Minister Richard Seddon’s motion to the House of

Representatives received overwhelming support. Following the motion’s adoption

the members rose to sing “God Save the Queen” and gave three cheers for Queen

Victoria. Seddon referred to New Zealanders’ duty “as Englishmen to support the

imperial cause.” New Zealand sent almost 6500 men and 8000 horses to South

Africa. The First Contingent arrived on 23rd November 1899 and was

quickly followed by four more contingents early in 1900. When it appeared that

the war was likely to be prolonged beyond the optimistic forecasts of the

middle of 1900, further fresh troops were sent, the Sixth Contingent arriving

in East London on 13th March and the Seventh in Durban on 10th

May 1901.

Throughout

the war there was no shortage of volunteers for service in South Africa. The

medical examination became more systematic as the war progressed and the large

number of volunteers meant that the doctors could be quite strict in their

assessment of medical status. Dental fitness was a matter of real concern. The

shooting test does not seem to have been particularly onerous but most

‘dejected rejecteds’ were those who failed the riding test. Early contingents

were very short of up-to-date equipment and at first were equipped with

single-shot Martini-Enfield carbines but by 1901 they were all using

Lee-Enfield or Lee-Metford magazine rifles. The Sixth Contingent, arriving at

East London and ordered very promptly to the front were without water bottles.

The quartermaster took 50 men to a local hotel, purchased 500 empty wine

bottles and pressed them into service for the contingent.

Throughout

the war there was no shortage of volunteers for service in South Africa. The

medical examination became more systematic as the war progressed and the large

number of volunteers meant that the doctors could be quite strict in their

assessment of medical status. Dental fitness was a matter of real concern. The

shooting test does not seem to have been particularly onerous but most

‘dejected rejecteds’ were those who failed the riding test. Early contingents

were very short of up-to-date equipment and at first were equipped with

single-shot Martini-Enfield carbines but by 1901 they were all using

Lee-Enfield or Lee-Metford magazine rifles. The Sixth Contingent, arriving at

East London and ordered very promptly to the front were without water bottles.

The quartermaster took 50 men to a local hotel, purchased 500 empty wine

bottles and pressed them into service for the contingent.

Commanding

the Seventh Contingent was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Porter, an outstanding, if

somewhat controversial character. His only active service had been in the

various campaigns in New Zealand from 1863 to 1871. He was 58 years old when he

came to South Africa. In South Africa he was mentioned in dispatches and

appointed a C.B. for his service. He was still an active soldier in 1917 when

he would have been 74 years old.

Commanding

the Seventh Contingent was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Porter, an outstanding, if

somewhat controversial character. His only active service had been in the

various campaigns in New Zealand from 1863 to 1871. He was 58 years old when he

came to South Africa. In South Africa he was mentioned in dispatches and

appointed a C.B. for his service. He was still an active soldier in 1917 when

he would have been 74 years old.The Seventh Contingent’s excellent record clearly reflected the fact that 12 officers and at least 6 NCO’s with previous service in South Africa sailed with the contingent. In addition, 69 men from previous contingents joined the Seventh in South Africa. These experienced men were without doubt one of the key reasons for the good record maintained by the later New Zealand contingents.

It

was in the Orange Free State where one of the most successful of the Boer

guerilla leaders, Christiaan de Wet, operated. De Wet may be said to have been

the first to advocate and demonstrate the hit-and-run strategy that the British

always found very difficult to counter. With the capture of Bloemfontein, and

later Pretoria, by Lord Roberts’s “steamroller” the Boers became very

dispirited. It was Christiaan de Wet and President Marthinus Steyn who roused

the hopes of their people by a brilliant revival of the form of warfare which

was carried on by the Boers with varying success all over South Africa until

the end of the war in May 1902.

It

was in the Orange Free State where one of the most successful of the Boer

guerilla leaders, Christiaan de Wet, operated. De Wet may be said to have been

the first to advocate and demonstrate the hit-and-run strategy that the British

always found very difficult to counter. With the capture of Bloemfontein, and

later Pretoria, by Lord Roberts’s “steamroller” the Boers became very

dispirited. It was Christiaan de Wet and President Marthinus Steyn who roused

the hopes of their people by a brilliant revival of the form of warfare which

was carried on by the Boers with varying success all over South Africa until

the end of the war in May 1902.

De

Wet was respected for his savage determination. He imposed severe discipline on

his commandos making them fear him and obey orders. Stories of keeping his men

in order with the sjambok are probably exaggerated. He seldom told them what it

was he intended and worked entirely on his own schemes. There was little in the

way of a strategic plan and he operated by surprise marches, attacking the

enemy’s weak points, cutting the railways, seizing their isolated garrisons and

skillfully avoiding capture by rapid flight from pursuing columns. That de Wet

remained at large was an astounding feat since he was always in the thick of

the fighting and many times had been very close to capture. He never stayed

long with any one commando and continually kept moving to give his commandos

directions.

De

Wet was respected for his savage determination. He imposed severe discipline on

his commandos making them fear him and obey orders. Stories of keeping his men

in order with the sjambok are probably exaggerated. He seldom told them what it

was he intended and worked entirely on his own schemes. There was little in the

way of a strategic plan and he operated by surprise marches, attacking the

enemy’s weak points, cutting the railways, seizing their isolated garrisons and

skillfully avoiding capture by rapid flight from pursuing columns. That de Wet

remained at large was an astounding feat since he was always in the thick of

the fighting and many times had been very close to capture. He never stayed

long with any one commando and continually kept moving to give his commandos

directions.

Throughout

1900 his successes mounted – Sanna’s Post, Mostert’s Hoek but a reverse at Wepener.

There the British force, mostly Colonial troops, put up a stout defence. De

Wet’s attacks continued and on 7th June 1900 his commando succeeded

in overwhelming a small British force at Roodewal Station. The Boers captured a

huge quantity of stores said to value anything up to £250 000. (De Wet in his

book “Three Years’ War” said £750 000!) What they could not carry away was

burnt, including the army mail. Communications between Pretoria and Kroonstad were

cut and the rail line for several miles was completely broken up.

Throughout

1900 his successes mounted – Sanna’s Post, Mostert’s Hoek but a reverse at Wepener.

There the British force, mostly Colonial troops, put up a stout defence. De

Wet’s attacks continued and on 7th June 1900 his commando succeeded

in overwhelming a small British force at Roodewal Station. The Boers captured a

huge quantity of stores said to value anything up to £250 000. (De Wet in his

book “Three Years’ War” said £750 000!) What they could not carry away was

burnt, including the army mail. Communications between Pretoria and Kroonstad were

cut and the rail line for several miles was completely broken up.

In

December 1900 Lord Roberts, in Durban and on his way back to England, told a

gathering that the war was practically over. President Kruger, after living

some weeks as a fugitive in a railway carriage, had left for Europe aboard a Dutch

warship. However, Louis Botha, Koos de la Rey and Christiaan de Wet were still

at large with bands of guerilla fighters. Roberts had given orders that Boer

farms were to be burnt as a way of denying them food. The war was practically

over – the war of set-piece battles. But a new war, just as costly in time and

human lives, and far more bitter, had only just begun.

In

December 1900 Lord Roberts, in Durban and on his way back to England, told a

gathering that the war was practically over. President Kruger, after living

some weeks as a fugitive in a railway carriage, had left for Europe aboard a Dutch

warship. However, Louis Botha, Koos de la Rey and Christiaan de Wet were still

at large with bands of guerilla fighters. Roberts had given orders that Boer

farms were to be burnt as a way of denying them food. The war was practically

over – the war of set-piece battles. But a new war, just as costly in time and

human lives, and far more bitter, had only just begun.

In

deciding to wage guerilla warfare, the Boers took note that they were

well-mounted and possessed of the best modern weapons. They were unconvinced of

any tactical inferiority to the invaders of their countries. They undertook

what became a long, heroic struggle adapted to the existing military

organization of the two Republics. Throughout this new war, for that is what is

was, the political and military control of their forces remained intact. The

Boers retained their tactical superiority wherever numbers were even

approximately even. For the British, this required the development and application

of an entirely new technology and strategy.

In

deciding to wage guerilla warfare, the Boers took note that they were

well-mounted and possessed of the best modern weapons. They were unconvinced of

any tactical inferiority to the invaders of their countries. They undertook

what became a long, heroic struggle adapted to the existing military

organization of the two Republics. Throughout this new war, for that is what is

was, the political and military control of their forces remained intact. The

Boers retained their tactical superiority wherever numbers were even

approximately even. For the British, this required the development and application

of an entirely new technology and strategy.

The

new British commander, General Lord Kitchener’s first priority was his lines of

communication, railways and telegraph lines. To protect the bridges along the railway

lines, the British built small stone forts or blockhouses at strategic points.

These were usually two storeys high and had a garrison of up to thirty men

under a sergeant. However, they took too long to build, about three months, and

were far too costly at £800 to £1000 each.

The

new British commander, General Lord Kitchener’s first priority was his lines of

communication, railways and telegraph lines. To protect the bridges along the railway

lines, the British built small stone forts or blockhouses at strategic points.

These were usually two storeys high and had a garrison of up to thirty men

under a sergeant. However, they took too long to build, about three months, and

were far too costly at £800 to £1000 each.

As

the Boer attacks on the railways became more numerous, something cheaper and

more quickly and easily erected was needed. Major Spring Rice of the Royal Engineers,

then in Middelburg, devised a blockhouse made of two concentric cylinders of

corrugated iron filled with shingle. These were proof at least against rifle

bullets and cost but £16. A party of six sappers with some African assistants

could complete a blockhouse, its ditch and wire entanglement in six hours.

Construction crews could build three blockhouses per day.

As

the Boer attacks on the railways became more numerous, something cheaper and

more quickly and easily erected was needed. Major Spring Rice of the Royal Engineers,

then in Middelburg, devised a blockhouse made of two concentric cylinders of

corrugated iron filled with shingle. These were proof at least against rifle

bullets and cost but £16. A party of six sappers with some African assistants

could complete a blockhouse, its ditch and wire entanglement in six hours.

Construction crews could build three blockhouses per day.

By

June 1901 lines of these small forts extended along all the railway lines and a

start was made on cross-country lines which had a different purpose. They were

to be barriers to the free movement of the Boer commandos who were now to be

driven and cornered against them. The country was to be divided into fenced

areas of manageable size within which the Boers could be dealt with piecemeal.

More than 8000 blockhouses had been erected by the war’s end.

By

June 1901 lines of these small forts extended along all the railway lines and a

start was made on cross-country lines which had a different purpose. They were

to be barriers to the free movement of the Boer commandos who were now to be

driven and cornered against them. The country was to be divided into fenced

areas of manageable size within which the Boers could be dealt with piecemeal.

More than 8000 blockhouses had been erected by the war’s end.

This

system was devised when it was realised that British “flying columns”, composed

mainly of infantry, with guns, field hospitals, engineers and a cumbersome

train of ox wagons, were hardly that. De Wet ordered that these columns should

not be opposed and the burghers ran few risks of capture for the British had

very few mounted men. The British walked where they liked and the Boers rode

where they pleased. Boer attacks on weak points and the railways continued. The

campaign might have continued for ten years had some new way of countering the

fleet-footed Boers not been evolved.

This

system was devised when it was realised that British “flying columns”, composed

mainly of infantry, with guns, field hospitals, engineers and a cumbersome

train of ox wagons, were hardly that. De Wet ordered that these columns should

not be opposed and the burghers ran few risks of capture for the British had

very few mounted men. The British walked where they liked and the Boers rode

where they pleased. Boer attacks on weak points and the railways continued. The

campaign might have continued for ten years had some new way of countering the

fleet-footed Boers not been evolved.

Over

the last few months of 1900 and the early months of 1901, de Wet and more

especially President Marthinus Steyn of the Orange Free State Republic were

engaged in reorganizing their demoralized commandos. By the middle of 1901 the

British were throwing much of their considerable resources into attempts to

corner de Wet as well as the Free State government.

Over

the last few months of 1900 and the early months of 1901, de Wet and more

especially President Marthinus Steyn of the Orange Free State Republic were

engaged in reorganizing their demoralized commandos. By the middle of 1901 the

British were throwing much of their considerable resources into attempts to

corner de Wet as well as the Free State government.

Steyn

came very close to capture in Reitz on 11th July 1901. His scouts

had reported that Colonel Broadwood’s column was five miles away and headed

towards Bethlehem. Thus Steyn and his government went to sleep in the deserted

town. Just after midnight Broadwood turned around and galloped back into Reitz.

The haul was 29 prisoners but President Steyn and his groom, a coloured lad

named Ruiter, managed to evade the crowd of British soldiers and gallop out of

the town.

Steyn

came very close to capture in Reitz on 11th July 1901. His scouts

had reported that Colonel Broadwood’s column was five miles away and headed

towards Bethlehem. Thus Steyn and his government went to sleep in the deserted

town. Just after midnight Broadwood turned around and galloped back into Reitz.

The haul was 29 prisoners but President Steyn and his groom, a coloured lad

named Ruiter, managed to evade the crowd of British soldiers and gallop out of

the town.

Steyn

was wearing only a nightshirt and had only a halter for a bridle. At the farm

of one de Jager, the lady of the house gave him her husband’s wedding suit and

one of his scouts had a spare hat. Almost the entire Free State government was

captured that night but Steyn soon formed a new executive. De Wet too was not

in Reitz that night, he had preferred his favourite farm Blijdschap, a few

miles to the west.

Steyn

was wearing only a nightshirt and had only a halter for a bridle. At the farm

of one de Jager, the lady of the house gave him her husband’s wedding suit and

one of his scouts had a spare hat. Almost the entire Free State government was

captured that night but Steyn soon formed a new executive. De Wet too was not

in Reitz that night, he had preferred his favourite farm Blijdschap, a few

miles to the west.

By

November 1901 the principal centres of Boer resistance were the north-eastern

Free State, the highveld of the eastern Transvaal and the western Transvaal,

under de Wet, Louis Botha and Koos de la Rey. Kitchener decided to disregard de

la Rey and throw the bulk of his forces against Botha and de Wet. In the first

week of November there were 14 British columns in the Free State. Three columns

were in Winburg, Colonel Julian Byng was in Heilbron, Colonel Michael Rimington

in Standerton and Colonel Dartnell and the Imperial Light Horse at Harrismith.

By

November 1901 the principal centres of Boer resistance were the north-eastern

Free State, the highveld of the eastern Transvaal and the western Transvaal,

under de Wet, Louis Botha and Koos de la Rey. Kitchener decided to disregard de

la Rey and throw the bulk of his forces against Botha and de Wet. In the first

week of November there were 14 British columns in the Free State. Three columns

were in Winburg, Colonel Julian Byng was in Heilbron, Colonel Michael Rimington

in Standerton and Colonel Dartnell and the Imperial Light Horse at Harrismith.

Kitchener’s

scheme was for all 14 columns to march inwards so as to converge on Paardehoek,

a farm south of Frankfort, where de Wet had summoned the commandos to assemble.

Extraordinary precautions were taken to maintain secrecy and even the officers

commanding the various columns knew nothing of the objective until the march

actually began. Efforts were made to deceive the Boers as to what was intended.

The columns moved smoothly and on 12th November the circle of

columns duly converged on Paardehoek and found the trap empty. During the drive

they had neither seen nor heard of any large hostile body. Boer intelligence

and mobility had been equal to the occasion and they had escaped through the

gaps in the cordon, particularly at night.

Kitchener’s

scheme was for all 14 columns to march inwards so as to converge on Paardehoek,

a farm south of Frankfort, where de Wet had summoned the commandos to assemble.

Extraordinary precautions were taken to maintain secrecy and even the officers

commanding the various columns knew nothing of the objective until the march

actually began. Efforts were made to deceive the Boers as to what was intended.

The columns moved smoothly and on 12th November the circle of

columns duly converged on Paardehoek and found the trap empty. During the drive

they had neither seen nor heard of any large hostile body. Boer intelligence

and mobility had been equal to the occasion and they had escaped through the

gaps in the cordon, particularly at night.

Following

the Reitz incident, the government party had become very cautious, rarely

sleeping in the same place on successive nights. Steyn and de Wet met at

Blijdschap on 16th November. A letter had arrived from Louis Botha

suggesting that this might be a favourable moment for the opening of overtures

for peace on the basis of the independence of the Boer republics. Botha had

enjoyed a smashing success at Bakenlaagte on 30th October which may

have prompted the letter. Steyn, of course, returned a characteristically fiery

reply. De Wet now decided to take the field and attacked the Imperial Light

Horse at Tyger Rivier Poort on 18th December but was forced to

retire into the Langberg. Wessel Wessels had a success at Tafelkop on 20th

December but de Wet dealt the British a stunning blow in the early hours of Christmas

morning, 1901. The attack was nade on a force of 500 Imperial Yeomanry encamped

on the top of a small hill called Groenkop, between Harrismith and Bethlehem.

Following

the Reitz incident, the government party had become very cautious, rarely

sleeping in the same place on successive nights. Steyn and de Wet met at

Blijdschap on 16th November. A letter had arrived from Louis Botha

suggesting that this might be a favourable moment for the opening of overtures

for peace on the basis of the independence of the Boer republics. Botha had

enjoyed a smashing success at Bakenlaagte on 30th October which may

have prompted the letter. Steyn, of course, returned a characteristically fiery

reply. De Wet now decided to take the field and attacked the Imperial Light

Horse at Tyger Rivier Poort on 18th December but was forced to

retire into the Langberg. Wessel Wessels had a success at Tafelkop on 20th

December but de Wet dealt the British a stunning blow in the early hours of Christmas

morning, 1901. The attack was nade on a force of 500 Imperial Yeomanry encamped

on the top of a small hill called Groenkop, between Harrismith and Bethlehem.

The

British were engaged in completing the blockhouse line between those two towns.

Major Williams, the British commander, had no outposts lining the edge of the

precipitous western side of the hill. British intelligence had not discovered

any Boers the previous day and thought an attack unlikely, especially up the

steep western side.

The

British were engaged in completing the blockhouse line between those two towns.

Major Williams, the British commander, had no outposts lining the edge of the

precipitous western side of the hill. British intelligence had not discovered

any Boers the previous day and thought an attack unlikely, especially up the

steep western side.

The

unsuspecting British were taken completely by surprise. They suffered 145

casualties in the fight, including 57 killed and de Wet left as dawn broke with

200 prisoners and two guns. A rider was sent to Elands River Bridge to summon

assistance but by the time the Imperial Light Horse had galloped the 12 miles

to the scene of the engagement, de Wet and his men were long gone.

The

unsuspecting British were taken completely by surprise. They suffered 145

casualties in the fight, including 57 killed and de Wet left as dawn broke with

200 prisoners and two guns. A rider was sent to Elands River Bridge to summon

assistance but by the time the Imperial Light Horse had galloped the 12 miles

to the scene of the engagement, de Wet and his men were long gone.

The

Free State president, Marthinus Steyn was now ailing. He was suffering from

ataxia, a nervous complaint, almost certainly caused by the strain that he had

undergone for almost two years. His sight was affected as well as his limbs and

riding a horse would have been difficult. His physical collapse was a

shattering experience. Around the village of Reitz were a number of farms where

they were safe from pursuit and Steyn stayed at Slabbert’s farm Rondebosch, to

the north east of Reitz for much of the first two months of 1902. The President

was able to rest at Rondebosch for some weeks and busy himself with the business

and correspondence of the Free State government. De Wet’s whereabouts needed to

be established before a decision was made by the British as to the direction of

the first attempt at the new model drive. His base near Elandskop, today’s

village of Petrus Steyn, was well-known but all attempts to nab him there had

thus far failed.

The

Free State president, Marthinus Steyn was now ailing. He was suffering from

ataxia, a nervous complaint, almost certainly caused by the strain that he had

undergone for almost two years. His sight was affected as well as his limbs and

riding a horse would have been difficult. His physical collapse was a

shattering experience. Around the village of Reitz were a number of farms where

they were safe from pursuit and Steyn stayed at Slabbert’s farm Rondebosch, to

the north east of Reitz for much of the first two months of 1902. The President

was able to rest at Rondebosch for some weeks and busy himself with the business

and correspondence of the Free State government. De Wet’s whereabouts needed to

be established before a decision was made by the British as to the direction of

the first attempt at the new model drive. His base near Elandskop, today’s

village of Petrus Steyn, was well-known but all attempts to nab him there had

thus far failed.

Colonel

Julian Byng camped at Fannie’s Home on a bluff overlooking the Liebenberg’s

Vlei river early in February 1902. Sending Lieutenant Colonel Garatt to

Armstrong Drift on the Liebenberg’s Vlei river, they came across the rear-guard

of a Boer force under Commandant Walter Mears on 3rd February. Mears

had been ordered to bring the guns, captured by de Wet at Groenkop on Christmas

Day, across the blockhouse line between Lindley and Bethlehem. Garatt’s men

included the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles who had “a hard gallop

and a running fight of some miles” in succeeding to rout the Boer rearguard and

recapture the lost guns. Major Bauchop, their commander, received a personal telegram

from Lord Kitchener and Garratt “gratified the New Zealanders by assuring them

that it was one of the best mounted charges he had ever seen.”

Colonel

Julian Byng camped at Fannie’s Home on a bluff overlooking the Liebenberg’s

Vlei river early in February 1902. Sending Lieutenant Colonel Garatt to

Armstrong Drift on the Liebenberg’s Vlei river, they came across the rear-guard

of a Boer force under Commandant Walter Mears on 3rd February. Mears

had been ordered to bring the guns, captured by de Wet at Groenkop on Christmas

Day, across the blockhouse line between Lindley and Bethlehem. Garatt’s men

included the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles who had “a hard gallop

and a running fight of some miles” in succeeding to rout the Boer rearguard and

recapture the lost guns. Major Bauchop, their commander, received a personal telegram

from Lord Kitchener and Garratt “gratified the New Zealanders by assuring them

that it was one of the best mounted charges he had ever seen.”

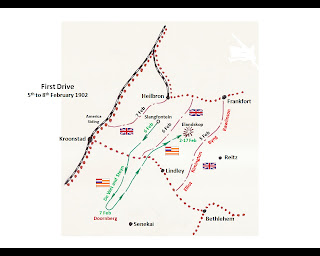

By

the beginning of February 1902 the lines of blockhouses in the north eastern

Free State were complete. Early in February 1902 the new system of sweeping

using the newly-encompassing blockhouse lines to the maximum was attempted. Up

until then the Boers had been able to pass the British lines when night fell

and gaps in the line opened up as the troops bivouacked. With the blockhouse

lines now complete and reinforced for the occasion of a drive, the mounted

troops would now form a continuous line ninety kilometres in length. The flanks

would be on a blockhouse line and the horsemen would maintain the line riding

straight ahead by day. At night every officer and every man would be on picquet

duty in a continuous entrenched line of picquets. In theory in this way there

would be no holes in the net and every Boer commando would be hedged in by the

line of horsemen, the blockhouses with their wire entanglements and armoured

trains on the railway lines. To maintain such a line over broken country with

hills and rivers to be crossed required discipline and skill, not to mention

endurance since the drives covered fifteen to twenty kilometres per day for a

week or more.

By

the beginning of February 1902 the lines of blockhouses in the north eastern

Free State were complete. Early in February 1902 the new system of sweeping

using the newly-encompassing blockhouse lines to the maximum was attempted. Up

until then the Boers had been able to pass the British lines when night fell

and gaps in the line opened up as the troops bivouacked. With the blockhouse

lines now complete and reinforced for the occasion of a drive, the mounted

troops would now form a continuous line ninety kilometres in length. The flanks

would be on a blockhouse line and the horsemen would maintain the line riding

straight ahead by day. At night every officer and every man would be on picquet

duty in a continuous entrenched line of picquets. In theory in this way there

would be no holes in the net and every Boer commando would be hedged in by the

line of horsemen, the blockhouses with their wire entanglements and armoured

trains on the railway lines. To maintain such a line over broken country with

hills and rivers to be crossed required discipline and skill, not to mention

endurance since the drives covered fifteen to twenty kilometres per day for a

week or more.

With

intelligence that de Wet was in the vicinity of Elandskop, the British line was

formed along the Liebenberg’s Vlei River in a line ninety kilometres long. The

sweep to the west as far as the main railway line was detected by de Wet’s

scouts and he moved south with his force of seven hundred men who had joined

him at Slangfontein. Managing to avoid the advancing British line they crossed

the Kroonstad-Lindley blockhouse line on the farm Doornkloof on the night of 6th

February heading for the Doornberg, north west of Senekal. The British swept on

westwards and closed off the area between America Siding on the main line and

Heilbron on the night of 7th February. Numbers of Boers were known

to be within the cordon and every possible means was used to ensure their

capture. Nearly three hundred were killed, wounded or captured.

With

intelligence that de Wet was in the vicinity of Elandskop, the British line was

formed along the Liebenberg’s Vlei River in a line ninety kilometres long. The

sweep to the west as far as the main railway line was detected by de Wet’s

scouts and he moved south with his force of seven hundred men who had joined

him at Slangfontein. Managing to avoid the advancing British line they crossed

the Kroonstad-Lindley blockhouse line on the farm Doornkloof on the night of 6th

February heading for the Doornberg, north west of Senekal. The British swept on

westwards and closed off the area between America Siding on the main line and

Heilbron on the night of 7th February. Numbers of Boers were known

to be within the cordon and every possible means was used to ensure their

capture. Nearly three hundred were killed, wounded or captured.

Lieutenant

Edward Gordon of the R.S.F. wrote in his diary of the last night of the drive:

“Firing almost continuous all night. There were undoubtedly a number of Boers

trying the line at various places all along to find good places for breaking

thro’. About eight armoured trains could be counted on the main line and the

Heilbron branch line, by their searchlights going all night. It was a wonderful

sight, like a great display of fireworks with the beams of searchlights

flashing all over the sky and a continual roar of rifle fire, punctuated by the

rattle of a Maxim or the report of a field gun. It was about the most wonderful

night I’ve ever spent and didn’t sleep a wink all night.”

Lieutenant

Edward Gordon of the R.S.F. wrote in his diary of the last night of the drive:

“Firing almost continuous all night. There were undoubtedly a number of Boers

trying the line at various places all along to find good places for breaking

thro’. About eight armoured trains could be counted on the main line and the

Heilbron branch line, by their searchlights going all night. It was a wonderful

sight, like a great display of fireworks with the beams of searchlights

flashing all over the sky and a continual roar of rifle fire, punctuated by the

rattle of a Maxim or the report of a field gun. It was about the most wonderful

night I’ve ever spent and didn’t sleep a wink all night.”

The

first drive had failed to capture their principal target but a second, much

larger scale drive was now planned. A segment of the Transvaal to the south of

the Natal railway would be the initial target when the line would wheel right

and sweep down the north eastern Free State between the Wilge River and the

Drakensberg. This time nearly thirty thousand troops were involved and the

drive would take nearly two weeks.

The

first drive had failed to capture their principal target but a second, much

larger scale drive was now planned. A segment of the Transvaal to the south of

the Natal railway would be the initial target when the line would wheel right

and sweep down the north eastern Free State between the Wilge River and the

Drakensberg. This time nearly thirty thousand troops were involved and the

drive would take nearly two weeks.

De

Wet, hearing that the coast was clear, had returned to Elandskop, crossing the

blockhouse line once again but this time under fire and losing two killed and

eight wounded. In preparation for the second drive, Major-General Elliot

reached Lindley on 16th February, making for the Wilge River as his

men were to form the line along the river.

De

Wet, hearing that the coast was clear, had returned to Elandskop, crossing the

blockhouse line once again but this time under fire and losing two killed and

eight wounded. In preparation for the second drive, Major-General Elliot

reached Lindley on 16th February, making for the Wilge River as his

men were to form the line along the river.

Receiving

intelligence of de Wet’s whereabouts near Elandskop, Elliot sent

Lieutenant-Colonel de Lisle to capture him but once again de Wet was not where

he was supposed to be. The following day de Wet rode eastwards and joined the

government at Rondebosch. President Steyn had remained there and had been well

outside the limits of the first drive. De Wet’s intelligence, for once was

faulty and on the approach of Elliot from the west he made the decision to

cross the Wilge River and try to break through the British line somewhere near

the Drakensberg. President Steyn and the government would have to come too as

Elliot’s men approached.

Receiving

intelligence of de Wet’s whereabouts near Elandskop, Elliot sent

Lieutenant-Colonel de Lisle to capture him but once again de Wet was not where

he was supposed to be. The following day de Wet rode eastwards and joined the

government at Rondebosch. President Steyn had remained there and had been well

outside the limits of the first drive. De Wet’s intelligence, for once was

faulty and on the approach of Elliot from the west he made the decision to

cross the Wilge River and try to break through the British line somewhere near

the Drakensberg. President Steyn and the government would have to come too as

Elliot’s men approached.

On

the night of 22nd February they had reached the Cornelis River and

Commandant Manie Botha and his Vrede commando joined them. Botha told them of

the British force sweeping in a line from the Wilge to the Drakensberg. They

were thus in danger of being trapped against the Bethlehem-Harrismith

blockhouse line. Shortly they were joined by two more Commandants, Alexander

Ross and his men from Frankfort as well as Hendrik Alberts and some men from Heidelberg.

There were also significant numbers of people and their animals who had left

their farms and were fleeing southwards.

On

the night of 22nd February they had reached the Cornelis River and

Commandant Manie Botha and his Vrede commando joined them. Botha told them of

the British force sweeping in a line from the Wilge to the Drakensberg. They

were thus in danger of being trapped against the Bethlehem-Harrismith

blockhouse line. Shortly they were joined by two more Commandants, Alexander

Ross and his men from Frankfort as well as Hendrik Alberts and some men from Heidelberg.

There were also significant numbers of people and their animals who had left

their farms and were fleeing southwards.

On

the 23rd the crowd followed the commandos as they moved along the right

bank of the Cornelis River. By late afternoon they had arrived at the farm

Brakfontein to the south of the Witkoppe. De Wet had intended to skirt the Witkoppe

to the east and travel north up the valley to Strydplaas but his scouts told

him that the British held a strong position at the head of the valley. Unable

to delay until the next morning, de Wet resolved to break through the British

line at Kalkkloof. Colonel Michael Rimington’s line stretched from Pramkop,

which practically overlooked the Wilge River, to Mooifontein where it joined

with Colonel Julian Byng. From Vrede southwards the country is rolling

grassland and the columns were able to maintain their line with little

difficulty. The line swept over the Bothasberg, low hills rather than mountains

as their name would seem to imply, but the Kalkkloof provided something more of

an obstacle. The right of Byng’s line, the 7th New Zealand Mounted

Rifles, filed down across the valley of the Holspruit and formed their line

along the crest of the next high ground to the south on the farm Langverwacht.

On

the 23rd the crowd followed the commandos as they moved along the right

bank of the Cornelis River. By late afternoon they had arrived at the farm

Brakfontein to the south of the Witkoppe. De Wet had intended to skirt the Witkoppe

to the east and travel north up the valley to Strydplaas but his scouts told

him that the British held a strong position at the head of the valley. Unable

to delay until the next morning, de Wet resolved to break through the British

line at Kalkkloof. Colonel Michael Rimington’s line stretched from Pramkop,

which practically overlooked the Wilge River, to Mooifontein where it joined

with Colonel Julian Byng. From Vrede southwards the country is rolling

grassland and the columns were able to maintain their line with little

difficulty. The line swept over the Bothasberg, low hills rather than mountains

as their name would seem to imply, but the Kalkkloof provided something more of

an obstacle. The right of Byng’s line, the 7th New Zealand Mounted

Rifles, filed down across the valley of the Holspruit and formed their line

along the crest of the next high ground to the south on the farm Langverwacht.

To

join up with the left of Rimington’s line, Lieutenant-Colonel Cox’s 3rd

New South Wales Mounted Rifles, they had to stretch their line so as to reach

up a kloof leading to the farm Mooifontein and Rimington’s line which was north

of the Holspruit. At the head of the kloof, Captain A.R.G. Begbie of the Royal Garrison

Artillery placed a pom pom gun in a small redoubt of stones that they quickly

erected.

To

join up with the left of Rimington’s line, Lieutenant-Colonel Cox’s 3rd

New South Wales Mounted Rifles, they had to stretch their line so as to reach

up a kloof leading to the farm Mooifontein and Rimington’s line which was north

of the Holspruit. At the head of the kloof, Captain A.R.G. Begbie of the Royal Garrison

Artillery placed a pom pom gun in a small redoubt of stones that they quickly

erected.

They

were entrenched in picquets of six men but inevitably there was a small gap

where the line crossed the Holspruit. This stream, like all the rivers and

streams in the vicinity, has high banks, something of a barrier to the easy

passage of horses and vehicles. The Boer multitude left Brakfontein once it was

dark and retraced their steps of that afternoon along the valley of the

Cornelis River. The commandos led the way followed by the crowd of carts and

spiders and the herds of cattle and horses. They arrived at the Holspruit at

midnight. De Wet and Steyn and his mule wagon crossed over at a ford. The

commandos skirted the road to the east. The three commandos would have

constituted a force of seven hundred men and they were mostly veteran soldiers.

They advanced in two groups, one quietly up the bed of the Holspruit.

They

were entrenched in picquets of six men but inevitably there was a small gap

where the line crossed the Holspruit. This stream, like all the rivers and

streams in the vicinity, has high banks, something of a barrier to the easy

passage of horses and vehicles. The Boer multitude left Brakfontein once it was

dark and retraced their steps of that afternoon along the valley of the

Cornelis River. The commandos led the way followed by the crowd of carts and

spiders and the herds of cattle and horses. They arrived at the Holspruit at

midnight. De Wet and Steyn and his mule wagon crossed over at a ford. The

commandos skirted the road to the east. The three commandos would have

constituted a force of seven hundred men and they were mostly veteran soldiers.

They advanced in two groups, one quietly up the bed of the Holspruit.

The

New Zealanders had heard the noise of the Boer multitude for some time and were

alert. The sentries had heard the “lowing of cattle, the rumbling of wagons and

the voices of women” and roused the men who were sleeping after a good meal of

roast sheep. The Boers in the donga, the bed of the Holspruit managed to get in

behind the line while the rest of the force rushed one of the pickets. Ross and

Manie Botha and their men now turned left and advanced along the line of

trenches in a half-circle. The New Zealanders were concerned about hitting

their own men if they fired along the trench line but soon put up a stout

resistance although under fire from all sides. “The fire was something

terrific. Bullets! They were just like hail stones falling on cabbage leaves”

wrote Trooper Lytton Ditely from the hospital in Harrismith where he was taken

after the fight.

The

New Zealanders had heard the noise of the Boer multitude for some time and were

alert. The sentries had heard the “lowing of cattle, the rumbling of wagons and

the voices of women” and roused the men who were sleeping after a good meal of

roast sheep. The Boers in the donga, the bed of the Holspruit managed to get in

behind the line while the rest of the force rushed one of the pickets. Ross and

Manie Botha and their men now turned left and advanced along the line of

trenches in a half-circle. The New Zealanders were concerned about hitting

their own men if they fired along the trench line but soon put up a stout

resistance although under fire from all sides. “The fire was something

terrific. Bullets! They were just like hail stones falling on cabbage leaves”

wrote Trooper Lytton Ditely from the hospital in Harrismith where he was taken

after the fight.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)